With Flink Statefun a powerful, polyglot data streaming framework has entered the real-time data processing landscape. It allows to break down a streaming pipeline into individual microservices which can each take care of one or more tasks. This post is about how to test these services individually without executing the whole pipeline.

The development of Stateful Functions is quite straight-forward thanks to extensive documentation and a couple of useful examples in the Statefun Playground repository. It is easy to create a graph of function services to express a complex streaming logic. However, it quickly becomes difficult to verify if the logic is implemented correctly or what the cause of a certain issue is. Before realizing it, the developers find themselves trapped in the cobweb of functions which process messages and send more messages to others. Not everything can be tackled with low-level unit tests and so only the option remains to start the full streaming pipeline with all services and see where messages come and go and what is written to logs.

In this post a more manageable approach is demonstrated how one can test the individual Stateful Functions in isolation. Every Stateful Function is a web service and can be tested like one. The only tricky part lies in understanding what input data structures it expects and what its responses look like. This covers the stage of “component tests” or “service tests” as described in Mike Cohn’s test pyramid.

This is also a good layer for performance tests, because they can be enriched by attaching a profiler and can be rerun without changes even after the major refactorings in the course of performance optimizations. How this can be done for a Flink statefun service is also shown below.

Contents

- The communication protocol of a Stateful Function call

- Understanding how the RequestReplyHandler works

- The “Greeter” example

- Building the example Service

- Sending a request to the example service

- Writing component tests with Pytest

- Load testing

- Summary

The communication protocol of a Stateful Function call

Stateful Functions are normal web services for which tailored contract tests, functional tests and performance tests can be implemented, covering the important edge cases and branches of the streaming logic. What makes this a bit harder than usual is the data flow imposed by the Statefun architecture.

The input of the web service is binary data coming as HTTP Post requests from the Statefun runtime. The API has to forward the payload to the RequestReplyHandler of the Flink Statefun SDK. This deserializes the data and translates it into native function calls to the actual function implementations. The code we want to test is in the API component and in the Stateful Function component. The other participants of a function call are provided by the framework. So we can run unit tests by mocking out the foreign parts and concentrating on either the API or the Stateful Function component. But how can we guarantee that it all fits together? We need a component test, a functional test for the whole flow of the request!

Understanding how the RequestReplyHandler works

If we can demystify how the payload of the HTTP request looks like, we can send HTTP requests against the web service and validate the correct handling of the whole request flow. The key to understanding is a view into the code of the RequestReplyHandler (simplified):

class RequestReplyHandler(object):

# ...

async def handle_async(self, request_bytes: bytes) -> bytes:

# 1. Parse request payload

pb_to_function = ToFunction()

pb_to_function.ParseFromString(request_bytes)

# 2. Extract the target address and find the matching function

pb_target_address = pb_to_function.invocation.target

sdk_address = sdk_address_from_pb(pb_target_address)

target_fn: StatefulFunction = self.functions.for_typename(sdk_address.typename)

# 3. Invoke the batch of statefun calls

ctx = UserFacingContext(sdk_address, res.storage)

fun = target_fn.fun

pb_batch = pb_to_function.invocation.invocations

for pb_invocation in pb_batch:

msg = Message(target_typename=sdk_address.typename, target_id=sdk_address.id,

typed_value=pb_invocation.argument)

ctx._caller = sdk_address_from_pb(pb_invocation.caller)

await fun(ctx, msg)

# 4. Collect the results

pb_from_function = collect_success(ctx)

return pb_from_function.SerializeToString()

The code is reduced to the core logic as far as we need to understand it. The input of handle_async is just the raw binary data from the HTTP request body. The steps are as follows:

- Deserialize the binary data as a protobuf object of the type

ToFunction. - The

ToFunctionobject contains not only the data for a function call but also the “address”, i.e. the name of the target function. This is extracted in the second step to find out which function to call. - Now the target function can be called. One

ToFunctionobject can hold the data for a whole batch of function calls which are executed sequentially in a loop. - Eventually all the results are collected and serialized into a protobuf object of the type

FromFunction.

The definition of the protobufs used are also available in the flink-statefun repository.

What we can take out of this is: We have to provide a ToFunction protobuf as input of the RequestReplyHandler and we will get a FromFunction protobuf as output. The same holds true for the whole web service, only that the protobuf objects in this case are wrapped into HTTP request and response.

The “Greeter” example

Before we continue with writing a first component test we need an example to play with. The training project flink-statefun-playground gives us a nice example pipeline with the main structural elements of a Flink Statefun system: Ingress and egress messages, messages between functions and local state. So it is a perfect setup to show how a test framework can be set up.

The sequence diagram below shows an example of the logical flow. It starts with a kafka message containing the name of some person. The message is forwarded as HTTP request to the first Stateful Function (“person”) by the Flink runtime. The function updates the state variable, prepares a message to the next Stateful Function sends both back in the HTTP response. The runtime parses the output, stores the state internally and forwards the new message to the next Stateful Function (“greeter”) as another HTTP request. The greeter function responds with a greeting as egress message in the HTTP response. This egress message is then pushed to Kafka by the statefun runtime.

So the Stateful Functions are normal web services with a request/response model. In addition the design is such that the functions are kept completely stateless. The state is maintained by the statefun runtime. This makes it very easy to test them.

For this post we will pick the “greeter” function and show how the HTTP requests by the Flink runtime can be simulated by a normal web service test framework. This way the endpoints of the Stateful Function can be validated.

Building the example Service

The goal is to test a single Stateful Function service in isolation without running an entire Flink pipeline. So we can take for example the go implementation of the greeter example and build it. The code shown below works without modification also for the Python implementation.

❯ docker build -t greeter-function .

Click to expand output…

Sending build context to Docker daemon 67.58kB

Step 1/11 : FROM golang:1.16-alpine

1.16-alpine: Pulling from library/golang

59bf1c3509f3: Pull complete

666ba61612fd: Pull complete

8ed8ca486205: Pull complete

ca4bf87e467a: Pull complete

0435e0963794: Pull complete

Digest: sha256:5616dca835fa90ef13a843824ba58394dad356b7d56198fb7c93cbe76d7d67fe

Status: Downloaded newer image for golang:1.16-alpine

---> 7642119cd161

Step 2/11 : RUN apk add --no-cache git

---> Running in cb271c1ec33c

fetch https://dl-cdn.alpinelinux.org/alpine/v3.15/main/x86_64/APKINDEX.tar.gz

fetch https://dl-cdn.alpinelinux.org/alpine/v3.15/community/x86_64/APKINDEX.tar.gz

(1/6) Installing brotli-libs (1.0.9-r5)

(2/6) Installing nghttp2-libs (1.46.0-r0)

(3/6) Installing libcurl (7.80.0-r0)

(4/6) Installing expat (2.4.7-r0)

(5/6) Installing pcre2 (10.39-r0)

(6/6) Installing git (2.34.2-r0)

Executing busybox-1.34.1-r3.trigger

OK: 19 MiB in 21 packages

Removing intermediate container cb271c1ec33c

---> 73f33e7acdea

Step 3/11 : RUN mkdir -p /app

---> Running in 90ab39692e73

Removing intermediate container 90ab39692e73

---> 78ee5bfb2ebd

Step 4/11 : WORKDIR /app

---> Running in 470afbeba332

Removing intermediate container 470afbeba332

---> 835d53bf431b

Step 5/11 : COPY go.mod ./

---> d2248af9b3d6

Step 6/11 : COPY go.sum ./

---> 129e125bff3a

Step 7/11 : RUN go mod download

---> Running in e05d848f3629

Removing intermediate container e05d848f3629

---> f7438c6e328b

Step 8/11 : COPY *.go ./

---> 257c44fb7cab

Step 9/11 : RUN go build -o /greeter

---> Running in f366e1804d0b

Removing intermediate container f366e1804d0b

---> 88a27ed71aa1

Step 10/11 : EXPOSE 8000

---> Running in 4477a2a9ab23

Removing intermediate container 4477a2a9ab23

---> 1be6d7746ad5

Step 11/11 : CMD [ "/greeter" ]

---> Running in af0b297934ef

Removing intermediate container af0b297934ef

---> 0b92c735920f

Successfully built 0b92c735920f

Successfully tagged greeter-function:latest

Now we can start the container and the service is up and running, waiting for messages:

❯ docker run --rm -it -p 8000:8000 greeter-function

2022/04/15 13:20:10 registering Stateful Function example/person

2022/04/15 13:20:10 registering state specification {visits 1 Expiration{mode=none, duration=0s}}

2022/04/15 13:20:10 registering Stateful Function example/greeter

Sending a request to the example service

In order to test the service, the protobuf objects have to be compiled and sent in the request body. A small Python script does this job as follows:

"""single-request.py

Minimal example of sending a single request to a Stateful Function.

"""

import requests

import statefun

import statefun.utils

import statefun.wrapper_types

from statefun.request_reply_pb2 import Address, FromFunction, ToFunction

# Prepare the request

GREET_REQUEST_TYPE = statefun.make_json_type(typename="example/GreetRequest")

invocation = ToFunction.Invocation(

argument=statefun.utils.to_typed_value(

GREET_REQUEST_TYPE, {"name": "George", "visits": 3}

)

)

invocation_batch_request = ToFunction.InvocationBatchRequest(

target=Address(namespace="example", type="greeter", id="George"),

invocations=[invocation],

)

request_payload = ToFunction(invocation=invocation_batch_request)

# Send the request and receive the response

response = requests.post(

"http://localhost:8000/statefun", data=request_payload.SerializeToString()

)

# Parse and print the response

from_function = FromFunction()

from_function.ParseFromString(response.content)

print(f"{response.status_code=}")

print(f"{from_function=}")

The preparation part in this code example is a bit hard to read because of the nested character of the request. But it is just about creating a protobuf object step-by-step. Starting from the inside, the objects that are created and nested into each other are:

- A statefun message in json format, named

example/GreetRequest - An

Invocationprotobuf which represents an individual call to a Stateful Function - An

InvocationBatchRequestprotobuf which can hold one or more invocations (here just one) - A

ToFunctionprotobuf which holds the invocation batch request and constitutes the actual request payload

We can send this data to the Stateful Function in a HTTP POST request and get back a FromFunction protobuf which has a similarly nested structure as the output of the the script shows when we run it:

❯ python single-request.py

response.status_code=200

from_function=invocation_result {

outgoing_egresses {

egress_namespace: "io.statefun.playground"

egress_type: "egress"

argument {

typename: "io.statefun.playground/EgressRecord"

has_value: true

value: "{\"topic\":\"greetings\",\"payload\":\"Third time is the charm George\"}\n"

}

}

}

The response contains

- a

FromFunctionprotobuf - which contains

InvocationResultprotobufs - which may contain outgoing messages

In this case the response contains one egress message. But instead of forwarding it to Kafka as the Flink runtime would do it, for testing purposes we can analyze the response and maybe add some assert statements to check if the content is valid.

Writing component tests with Pytest

The example above can be turned into an end-to-end test of the Stateful Function quite easily, e.g. using the test framework pytest.

"""test-greeter.py

Minimal example of sending a single request to a Stateful Function.

"""

import json

import pytest

import requests

import statefun

import statefun.utils

import statefun.wrapper_types

from statefun.request_reply_pb2 import Address, FromFunction, ToFunction

@pytest.mark.parametrize(

"visit, expected_message",

[

(1, "Welcome George"),

(3, "Third time is the charm George"),

],

)

def test_correct_greeting(visit, expected_message):

# Prepare the request

GREET_REQUEST_TYPE = statefun.make_json_type(typename="example/GreetRequest")

invocation = ToFunction.Invocation(

argument=statefun.utils.to_typed_value(

GREET_REQUEST_TYPE, {"name": "George", "visits": visit}

)

)

invocation_batch_request = ToFunction.InvocationBatchRequest(

target=Address(namespace="example", type="greeter", id="George"),

invocations=[invocation],

)

request_payload = ToFunction(invocation=invocation_batch_request)

# Send the request and receive the response

response = requests.post(

"http://localhost:8000/statefun", data=request_payload.SerializeToString()

)

# Parse and print the response

from_function = FromFunction()

from_function.ParseFromString(response.content)

# Check the output

assert response.status_code == 200

egress_message = json.loads(

from_function.invocation_result.outgoing_egresses[0].argument.value

)

assert egress_message["topic"] == "greetings"

assert egress_message["payload"] == expected_message

This checks the correct HTTP response code (200) and the correct egress message depending on the number of prior visits. We can run it with:

❯ python -m pytest test-greeter.py

==================================================================== test session starts =====================================================================

platform linux -- Python 3.10.3, pytest-7.1.1, pluggy-1.0.0

collected 2 items

test-greeter.py ..

By the way: try to put in a negative or very large number. At least the Go implementation returns a HTTP 500 code and logs an exception. This is exactly the thing we want to find and remove by adding tests!

Load testing

In a final stage, let’s use the same setup and wrap it into a load testing tool to measure the performance of the service. We can use Locust for this very well. This framework provides a lean interface, into which we can easily wrap the Python code above. The result looks very similar to the Pytest example:

"""load_test.py

A simple load test of the Stateful Function.

"""

import random

import requests

import statefun

import statefun.utils

import statefun.wrapper_types

from locust import HttpUser, between, task

from statefun.request_reply_pb2 import Address, ToFunction

GREET_REQUEST_TYPE = statefun.make_json_type(typename="example/GreetRequest")

class WebsiteUser(HttpUser):

wait_time = between(0.01, 0.1)

@task

def greeter(self):

invocation = ToFunction.Invocation(

argument=statefun.utils.to_typed_value(

GREET_REQUEST_TYPE, {"name": "George", "visits": random.randint(1, 3)}

)

)

invocation_batch_request = ToFunction.InvocationBatchRequest(

target=Address(namespace="example", type="greeter", id="George"),

invocations=[invocation],

)

request_payload = ToFunction(invocation=invocation_batch_request)

self.client.post("/statefun", request_payload.SerializeToString())

This defines a WebsiteUser class which calls the greeter function, waits between 10 and 100 milliseconds and then does it again.

The load test can be run with:

locust -H "http://localhost:8000" --only-summary -f load_test.py

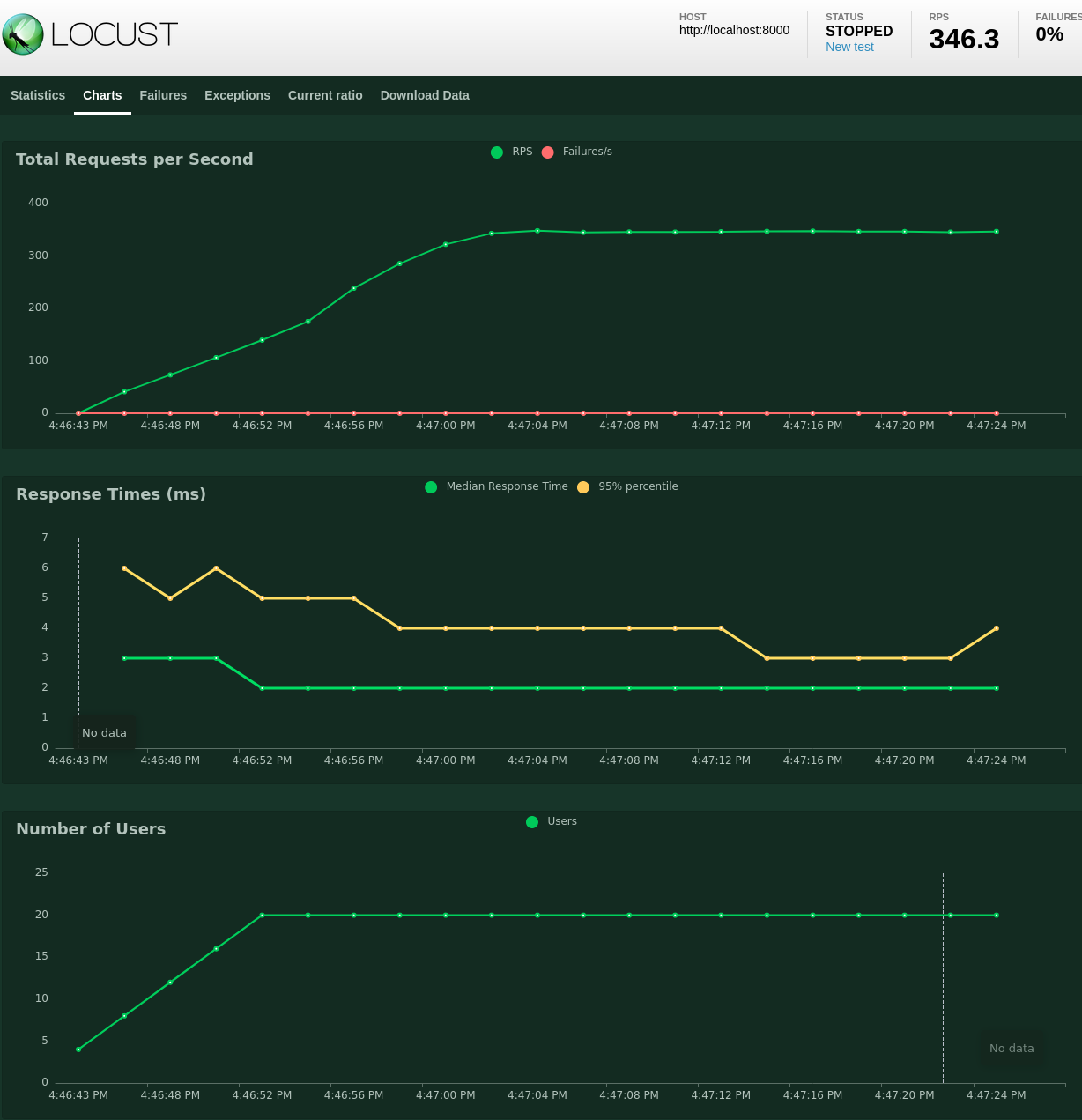

If we let it run for some time we get nice charts about the performance of the Stateful Function:

This is for 20 concurrent users and without any overhead of other components such as the Flink runtime or Kafka. So the one service can be evaluated and optimized in isolation.

Summary

This post shows how one can conduct component tests for an individual flink statefun service. This covers the middle-layer of a good test setup between unit tests and full end-to-end system tests of the entire Flink pipeline. The test harness requires some understanding of the communication protocols. But it isn’t too complicated and also allows to run performance and stress tests as basis for performance optimizations.

The complete source code is available on github.